Kragujevac - the forms of memory

„Racial-biologic protection of national living force and the family must be in the foundation of every state, social and economic policy" - programme of "Zbor" - Stevan Ivanić, the commissary for social policy and national health in the commissary government of Milan Nedić.

"Forgetting is... the key factor in the building of a nation" - Ernst Renan

The tragedy of political violence also contains the key to the mechanism generating that violence. The society slipping from its ethical plane is often clearly refracting in the seemingly minor, local events, which, as if by chance, reach the pinnacle of the ideologically pure violence, erasing every trace of civilization. The tragedy in Kragujevac, one of many during October 1941, contains such sub-event, its own ideologically pure vignette. The racially motivated hunt of the Roma, by the "Serbian State Guards" and its volunteers to gather the victims for the exchange of select Serbian hostages with the German occupiers. This event was conducted by Marisav Petrović, local fascist, the official of Dimitrije Ljotić's organization "Zbor", and the commander of the "Fifth Volunteer Batallion" with his unit, after taking over the local municipal authority, and aided the Wehrmacht punitive expedition to racially and ideologically select the victims for the mass executions - communists, workers, partisan sympathizers, Jews, Roma, the poor, the peasants, children, schoolboys, those that could be abducted, those that have had a grudge against as well as those they never met, members of their own extended families, the innocent, the naive and the accidental... This enumeration, seemingly complex and confusing, on the day, was far from arbitrary, but rather structured by a long-running education and habituation to chauvinism, racism, and the political violence against the unprotected ethnic and social groups. The testament to the degree of "normalcy" of their actions, as well as the degree of adoption of the Nazi ideology are the swiftness of the action, and the complete absence of any sign of the revolt, shame or compassion for the victims by the volunteers. These indicate a much earlier de-sensitization of the perpetrators and the dehumanization of their victims.

The “Crystal flower” (a monument to the shoe-shine boys)

The monument "Crystal flower" (the monument to the shoe-shine boys), by architect Nebojša Delja. Concrete, erected in 1968. Memorial park 21st. October, Šumarice, Kragujevac.

By the side of a mass-grave where the Roma shoe-shine boys aged 12 to 15, were shot, there is the monument "Crystal flower". "The geometrically reductive forms of the flower and the rounded forms it symbolizes the just-developed bud, cut in half. The whiteness of the flower emphasizes the moral purity of the boys, and the black cups, besides the color of their skin, associate the death and the darkness of the underworld." (official depiction). Two colors of the monument are often mentioned even among the professionals, and the material is frequently cited as marble, which is incorrect. The monument was made of concrete and painted in two tones. That paint is mostly faded today. The mass grave, unlike others, has no wall, and no memorial plaque was installed. The broken lighting was never replaced, and the Stella on the approach path with the engraved text is covered in lichen and unreadable. The Roma in Kragujevac are frequently expressing dissatisfaction with the subtitle of the monument - not all Roma children who perished were shoe-shine boys.

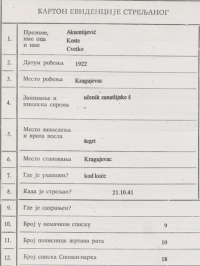

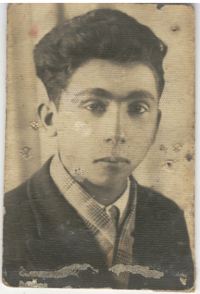

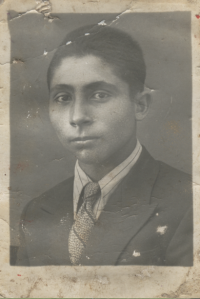

Sava and Cvetko Aksentijević

“CVETKO WORE AN ASHEN COLOURED COAT.”

“WHEN HE WAS TAKEN OUT TO BE SHOT, SAVA WORE A GREEN JACKET.”

There was a number of primary and secondary schools in Kragujevac before World War II. Two brothers, Sava and Cvetko Aksentijevic attended one of them. In the vocational school they attended, they were taught, in addition to general subjects, also special ones to help them get a job immediately after school. But after the introduction of racial laws, the Roma education was prohibited. Sava and Cvetko, like many others of their generation, were no longer able to attend school. It was difficult to find a job, because the Roma were also prohibited from getting work. They were also no longer issued identity cards.

Ministry of Education, the Curriculum Department:

“Pending the adoption of the new regulation on the education of children of Jews and Gypsies in the territory of the military commander of Serbia at the beginning of school year 1941/42, the admission of students who are of Jewish or Gypsy origin in schools under the remit of the Ministry of Education shall be suspended (...)” (Archives of Yugoslavia, 110-908-554)

Sava and Cvetko have been living with a family in Mišarska street, in the neighborhood known as "Licika". One day they were taken with all other Roma men from that neighborhood. Where were they taken After the war, Kosara Aksentijevic, Sava’s and Cvetko’s mother, gave the following statement to the Yugoslav Commission for the Investigation of War Crimes:

“The Germans, that is, their punitive expedition, took my two sons, Cvetko and Sava Aksentijevic, on 20th of October 1941 from our home and into the sheds of the Third Artillery Regiment. They spent the night there and the Germans shot them the following day. Cvetko was wearing an ashen-coloured short coat and matching trousers, all second-hand, a blue hat that I brought home, black shoes and a white shirt. When he was taken out to be shot, Sava wore a green jacket, new brown cloth trousers, black boots and a cream-coloured shirt.”

The officers of the German army were enforcing the already established, retaliation measures against civilians. This time, it was done in retaliation for the killing of 10 and wounding of 26 German soldiers a few days earlier. Such reprisals were carried out wherever an insurrection or armed struggle broke out, especially in October 1941. On the orders of their commanders, they shot 100 hostages for each German soldier or officer killed, and 50 for each one wounded. In collecting hostages, they usually first arrested communists, Jews, and Roma, or those people who, according to the Nazi ideology, had to be eliminated. Many Serbian civilians were shot together with them in Draginac, Kraljevo, Niš, Kragujevac...

The first day, on 19th of October, the German army shot about 800 people, mostly communists, and sympathizers of the communist party, Jews, prisoners, peasants from the nearby villages. The following day, the city was blocked and the mass arrests started in Kragujevac. On the morning of 20th of October, the German soldiers along with the Serbian volunteers” (the so-called Ljoticevci), arrested more than 200 Roma men, mostly in their homes. The Serbian volunteers used the opportunity to exchange hostages. To save their acquaintances, friends, and others, they gave the Germans in exchange for each two, three, and up to ten Roma.

Sava and Cvetko were executed along with other Roma. Some of them were children.

Milka Đorđević

“God forbid that this should ever happen to anyone…”

“Hold on to your freedom, hold on to it as hard as you can!“

On the eve of World War II, Milka, a young girl at the time, lived with her father, mother and brother. Shortly before the war, she lost her mother. At the time the war broke out, she, her father and brother were living in difficult economic conditions. In mid-October 1941, Milka’s father and younger brother were evicted from their home and taken away with other Roma men. In those days the German forces, with the help of local collaborators, gathered civilians in Kragujevac and the surrounding area and took them to be shot. Milka’s brother was singled out from the column along with a few boys of his age and was told by a German soldier to flee.

“I remember my father looking at me, taking his coat and climbing onto the truck. ...I never saw him again.”

Milka remained alone with her father’s new wife, her stepmother. Her brother returned after over a month, but their stepmother could not support them. She sent Milka to her daughter and her brother reported for work in Germany. At that time it was possible to volunteer for work there as the German Reich was in constant need of labour force. In addition to prisoners of war and civilians in forced labour, as well as detainees in the camps who were often forced to work to death, there was a possibility for workers from countries allied with Germany, as well as from the occupied territories to apply for work in Germany. Although the workers had contracts, many were working in adverse conditions and subsequently died. This is where Milka’s brother died too.

What was the situation like in Serbia? Life in Kragujevac was very difficult, people often feared for their lives:

“So many times we ran straight out of our beds that were still warm...”

“The bearded men [Chetniks] made us go and sleep with pigs.”

In October 1944, fighting was underway for the liberation of Kragujevac between the Germans and their allies on the one side and partisans and the Soviet Union’s Red Army on the other. There was fighting in town:

“I am among them, they [the Germans] are fleeing, leaving everything, candy, food, I take everything to the people in the basement [partisans], bullets keep flying over my head, but I have no fear.”

Milka was unable to attend school during the war. She enrolled only after the liberation, in Yugoslavia, and completed two grades. Then her cousin Mihailo Jovanovic returned from captivity. Milka got a job at a factory in Kragujevac and worked there until her retirement. At first, she performed physically strenuous work, but when the director realized this, he intervened and moved her to physically less demanding tasks. She worked hard and well. She received the best worker recognition (udarnicka karta) for her work. In the period immediately after the war, the government of socialist Yugoslavia used to reward, following the Soviet Union model, workers who excelled in performing their duties (the so-called udarnici). Milka soon gave birth to a son and a daughter. Milka now lives in Kragujevac, she is retired and has a daughter, a son and two grandchildren. Milka still remembers those difficult times and is willing to discuss it with anyone, even though she finds it all very strenuous and sad.

List of the victims, at the site of Memorial museum 21st October, Kragujevac: http://www.spomenpark.rs/rs/muzej-21-oktobar/spisak-streljanih

More on the mass-crime in Kragujevac, also on the site of the Center for Holocaust Research and Education: http://cieh-chre.org/kragujevac/#

Interview with Milka Đorđević

Contact: Center for Holocaust Research and Education - CHRE, tel: +38163247856, e-mail: [email protected] web: www.cieh-chre.org

* All parts of this website and project are the intellectual property of their authors, partner organizations and companies whose software and licenses and are used on the website, and as such enjoy the legal protection, so no third party can use them without the explicit permission of the authors. (This relates in particular to the concepts, methods and structural elements of the website, map, exhibitions, texts, and visual materials, but is not limited to, and does not exclude other derivatives and authors rights associated with them.) The use of the publication is governed by the Creative Commons license stated on the publication which is free to download.